Gout [1] is one of the most common causes of inflammatory arthritis worldwide, characterised by urate crystal deposition in the joint spaces. Previously recognized complications of gout include tophi, joint deformity, bone loss; renal disease such as nephrolithiasis, and ocular diseases such as conjunctivitis, uveitis, or scleritis [2].

In 2023, a study was published where a team of researchers performed an investigation of neuroimaging markers in patients with gout trying to establish a connection between gout and neurodegenerative disease risk [3]. It involves 11,735 patients diagnosed or self-reported with gout.

The imaging studies conducted included T1-weighted and T2-weighted-FLAIR structural imaging, susceptibility-weighted MRI and diffusion MRI. The studies give data on patients’ whole brain and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) volumes, cortical volumes, surface area, thickness, T2-FLAIR white matter hyperintensities (WMH) volumes, brain iron deposition metrics (T2* and magnetic susceptibility), white matter microstructural measures (Supplementary Methods). The incidence of neurodegenerative disease was defined from UK Biobank’s baseline assessment data collection and linked hospital patient records.

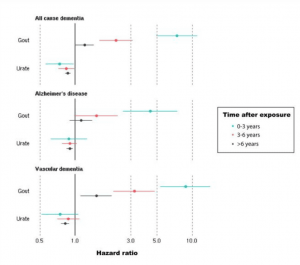

Results indicated that urate level was inversely associated with global brain volume, and also grey and (separately) white matter volumes, with corresponding higher cerebrospinal fluid volumes. In addition, gout and higher urate significantly associated with higher iron deposition of several basal ganglia structures, including bilateral putamen and caudate. It has been well established that iron deposition [4], and reduction in brain volume is a key marker for dementia and cognitive decline. From the observational data available, researchers further concluded that gout is associated with a higher incidence of dementia (average over study HR = 1.60 [1.38–1.85]), with the risk being highest in the first 3 years after onset of gout.

Interestingly, despite the majority of gout is caused by elevated level of serum urate, it does not carry a hazard ratio greater than 1 in majority of cases as detailed in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 Hazard ratios of incident dementia for gout (N = 303,149, 3126 dementia cases) and serum urate in asymptomatic participants (N = 247,328, 2454 dementia cases).

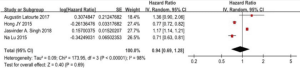

The author acknowledged that the underlying mechanism of how gout affects brain volume is unclear. They have also acknowledged that a recent meta-analysis [5] published by Pan et al. found no evidence for an association with gout overall, but could be a possible protective effect on Alzheimer’s disease. This meta-analysis included 4 eligible studies in this field conducted between 2015-2018 in China, France, UK and US with 121 136 patients with dementia. It concluded that across the 4 studies, there is no increased risk of dementia among patients with gout or hyperuricaemia with a pooled HR of 0.94, p<0.001.

Figure 2 Forest plot showing association between dementia and patients with gout and hyperuricaemia

Contrasting to the 2023 study, a 2021 study [6] conducted in Korea reported that gout was independently associated with a 37% lower risk of dementia in the elderly. The study included 22,178 and 113,590 dementia patients with and without gout respectively to investigate the relationship between gout and dementia. In their multivariable analysis, gout was independently associated with a lower hazard ratio (0.63) of developing dementia.

Coming back to our new study [3], despite having a large sample size with cutting edge imaging studies, it did not establish a causal effect of gout and neurodegenerative disease. The strong association indicated in the current data could be affected by other medical and/or lifestyle factors which have not been considered in this case. The author explained that ‘differing choice of single nucleotide polymorphisms as instrumental variables and outcome genome-wide association study between studies may explain the contradictory results.

This is an interesting area of research considering that gout affects 1-6.8% of world population [7], and dementia is one of the most disabling diseases in elderly. Future studies could consider the confounding medical and lifestyle factors that influence the outcome of gout and dementia, and potentially establish a causal link between the two conditions.

Reference

1.Fenando A, Widrich J. Gout. PubMed. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

2.Berman EL. Clues in the eye: ocular signs of metabolic and nutritional disorders. Geriatrics. 1995 Jul 1;50(7):34–6, 43–4.

3.Topiwala A, Kulveer Mankia, Bell S, Webb A, Ebmeier KP, Howard I, et al. Association of gout with brain reserve and vulnerability to neurodegenerative disease. 2023 May 18;14(1).

4.Liu JL, Fan YG, Yang ZS, Wang ZY, Guo C. Iron and Alzheimer’s Disease: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Implications. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2018 Sep 10;12.

5.Pan SY, Cheng RJ, Xia ZJ, Zhang QP, Liu Y. Risk of dementia in gout and hyperuricaemia: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ Open. 2021 Jun 22;11(6):e041680.

6.Min KH, Kang SO, Oh SJ, Han JM, Lee KE. Association Between Gout and Dementia in the Elderly: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2021 Jan;

7.Wen P, Luo P, Zhang B, Zhang Y. Mapping Knowledge Structure and Global Research Trends in Gout: A Bibliometric Analysis From 2001 to 2021. Frontiers in Public Health. 2022 Jun 29;10.